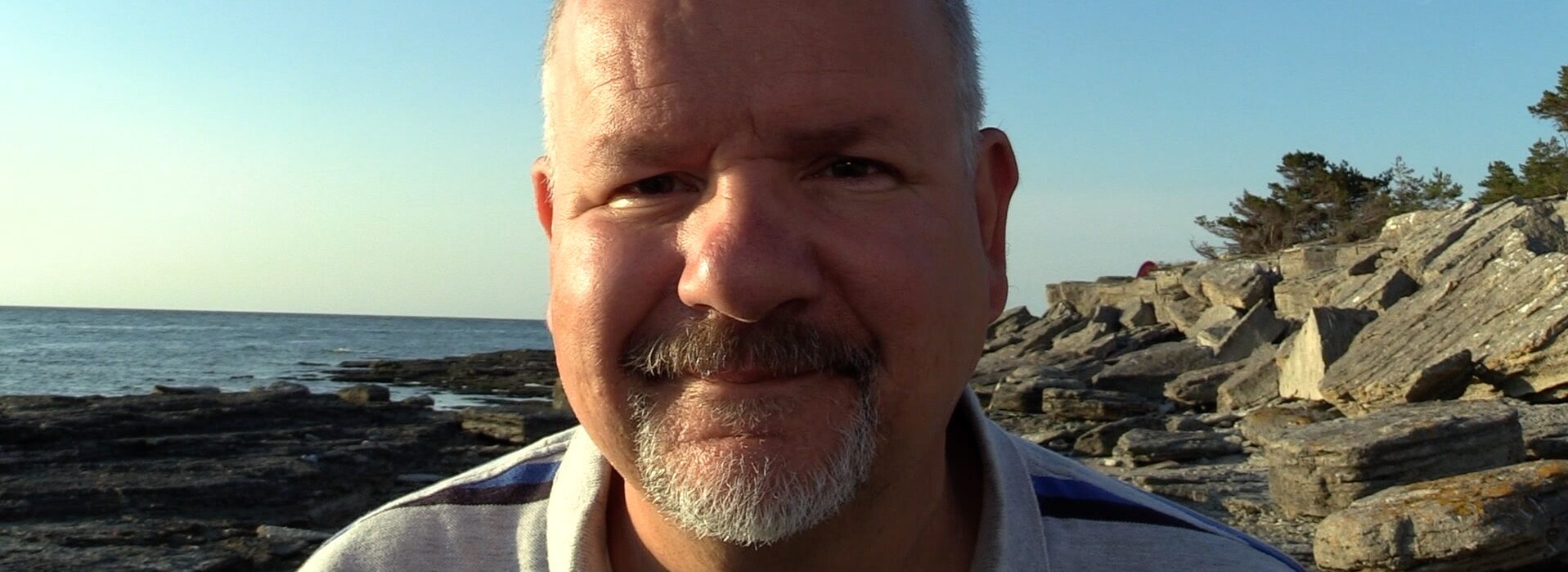

A story by: Martin Sundahl

Images by: Erik Fasth, Mats Holmstrand

My name is Martin Sundahl, and my passion is filmmaking!

At 20, I attended the Film and TV School in Kalix in Sweden and have since worked in various roles within film and video production. I’ve also had the opportunity to work as a studio photographer and as a special effects manager on an international feature film production. From the beginning of year 2000 I have also worked as a media teacher.

My passion for film and filmmaking began in the 1970s when I borrowed my father’s dual-8 camera. Over time, I transitioned from Super 8 to 16mm film and eventually to video technology.

In the late 1970s, I came into contact with a non-profit organization for film enthusiasts called Värmlands Filmförbund. It became a gateway to connecting with like-minded individuals, forming film teams, and gaining access to film equipment. The organization also offered invaluable support, making it possible to bring film ideas to life and turn creative visions into reality. In the Värmlands Filmförbund, as an impulsive teenager, I met older members who became role models through their passion for filmmaking. They gave me attention and encouragement, which, in turn, boosted my confidence and strengthened my belief in succeeding with what I wanted to create.

Filmmaking Before Smartphones

Creating a short film in the 1970s and 80s with Super 8 or 16mm film on a very low budget was a challenging but rewarding endeavor. It was a time when filmmaking was far from the digital ease of today, and every step demanded dedication, resourcefulness, and physical effort. Here’s a brief historical retrospective from my time as a filmmaker.

”Expressing myself through images has always been my greatest passion, and I continue to find it incredibly exciting and rewarding.”

The Struggles of Equipment

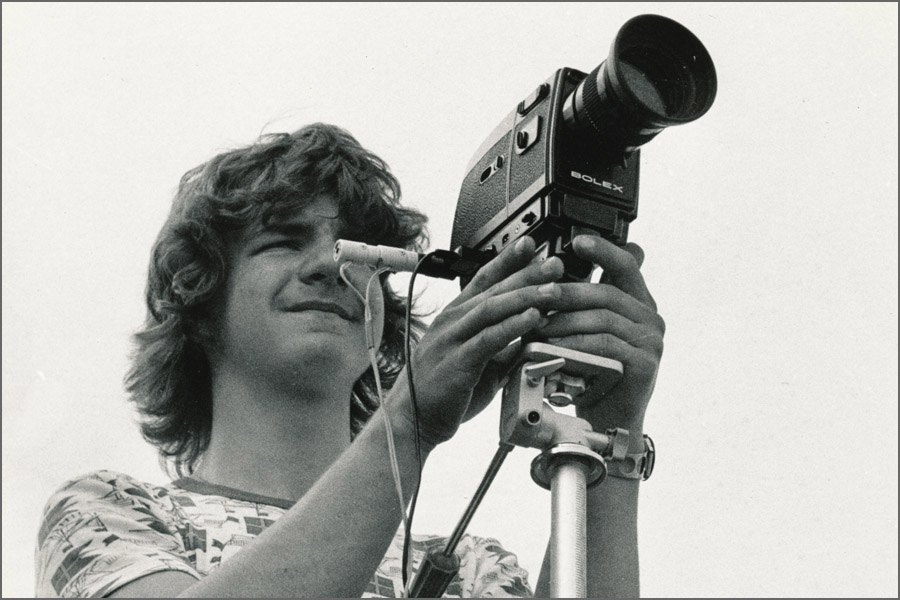

The cameras themselves were often heavy and cumbersome and nothing like the mobile phones often used today for filming. Super 8 cameras featured a compact film format that made them accessible and portable, but they offered lower picture resolution with less image detail and sharpness compared to the larger 16mm film.

Due to financial constraints, I primarily filmed with Super-8 in the late 1970s.

16mm film was significantly more expensive the Super 8 film, both in terms of the film stock itself and the costs of processing and equipment. They cameras were also bulkier, often requiring sturdy tripods and a steady hand for optimal use. Carrying these cameras, along with lenses, film reels, and sometimes a separate sound recorder, turned every shoot into a logistical challenge.

Later I had the opportunity to work with 16mm film.

Shooting on Film

Working with film stock added another layer of complexity. Each reel could only hold a few minutes of footage, forcing filmmakers to plan every shot meticulously. There was no instant playback to review a take—mistakes weren’t apparent until the film was developed, which could take days or weeks, depending on the budget and access to a lab. This meant that every second of shooting had to count, leaving no room for improvisation or excessive retakes.

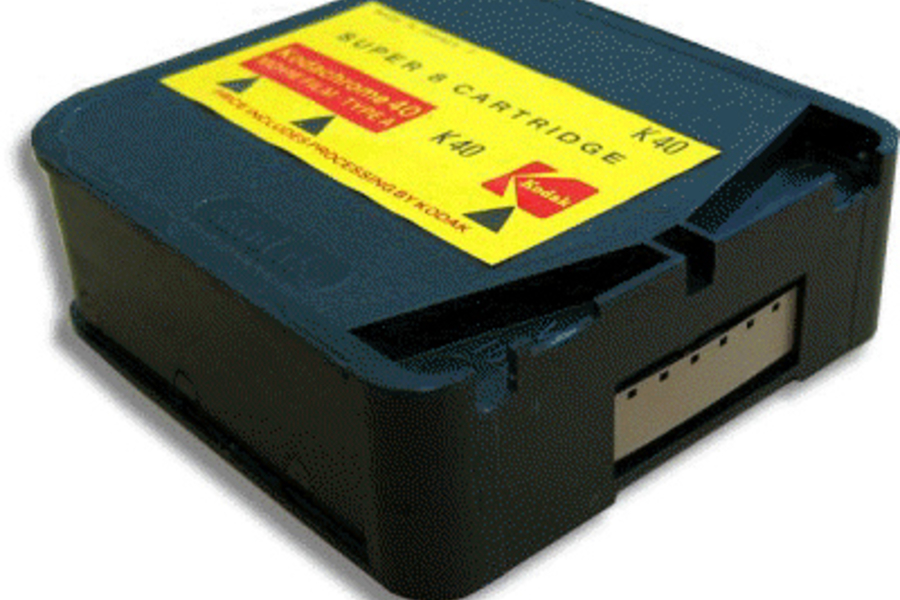

The Kodak Super8 cassette.

The Super-8 cassette, introduced already in 1965, revolutionized amateur filmmaking by offering a compact and easy-to-use film format. Each cassette contained 50 feet (about 3 minutes of footage at 18 frames per second) of film, eliminating the need to manually load and thread reels. Despite its convenience, costs could add up—film stock and processing typically ranged from $10 to $20 per cartridge in its heyday, making it a relatively expensive hobby for enthusiasts on a tight budget.

The Weight of Budget Constraints

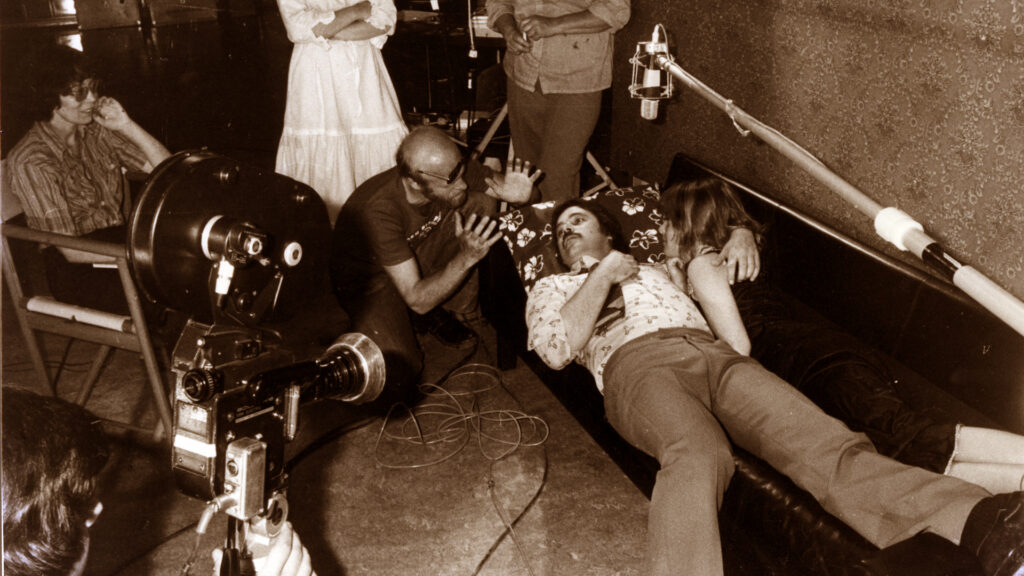

Low-budget filmmaking meant cutting corners wherever possible. I often borrowed or rented equipment, shot in friends’ houses or public spaces, and recruited non-professional actors who were willing to work for free. The organization Värmlands Filmförbund provided me with incredible support by giving access to essential film gear. Their resources made it possible for me to experiment, learn, and bring my creative ideas to life, even on a limited budget.

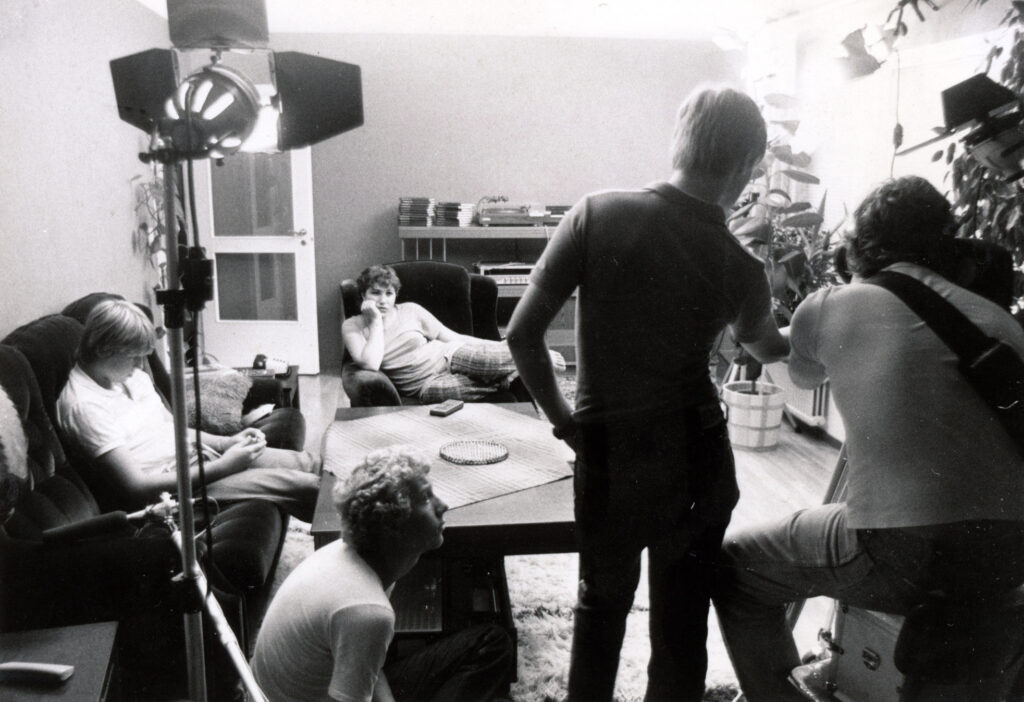

The need of light

When filming with traditional film cameras, there was a significant demand for ample lighting, as film stock had limited sensitivity to light. This often meant using powerful lights and carefully controlling the environment to ensure well-exposed footage. In contrast, modern video cameras have much higher light sensitivity, allowing for filming in lower light conditions without sacrificing image quality. With video cameras, it’s now possible to film in natural light with greater ease, thanks to their enhanced light sensitivity. This allows for more flexible shooting conditions without the need for extensive artificial lighting.

Much of the struggle with lighting the set was about chasing away shadows because the lights were so strong.

The Challenges of Sound in Filmmaking

Working with sound in filmmaking during the era of Super 8 and 16mm film was an intricate and demanding process, particularly for those on a tight budget. With no digital tools to simplify the workflow, capturing, mixing, and synchronizing sound was as much an art as it was a technical challenge.

Sound recording during production was often done using portable reel-to-reel tape recorders. ”Nagra” recorders were the gold standard, prized for their reliability and high-quality sound, but they were expensive and heavy. For low-budget productions, filmmakers often relied on cheaper alternatives, which came with limitations in sound fidelity.

Playing the tape, control listening between takes.

Perforated magnetic tape, or “perfotape,” was a common medium for syncing audio with film. Copying sound from 1/4-inch tape with a pilot tone to 16mm perfotape was a meticulous process. The basic principle is this: A small generator, connected to the camera’s drive shaft, generates an alternating current called a pilot tone, which maintains 50 Hz when the camera runs at 24 fps. If the camera’s frame rate changes, the pilot tone’s frequency also changes. This pilot tone is recorded on the audio tape on a separate channel, and what is captured there, along with the pilot tone, represents the camera’s speed relative to the speed of the audio tape.

Copying the sound from 1/4″ tape to ”16mm perfotape”.

When the sound is later transferred to perforated magnetic film (perfotape) after the day’s recording work, the pilot tone controls the speed of the transfer machine, ensuring it matches any speed variations of the camera and tape recorder. In this way, the perforated magnetic film becomes synchronized with the picture film.This tape was later laboriously edited by hand using splicing blocks and tape adhesive, much like the editing of the film itself.

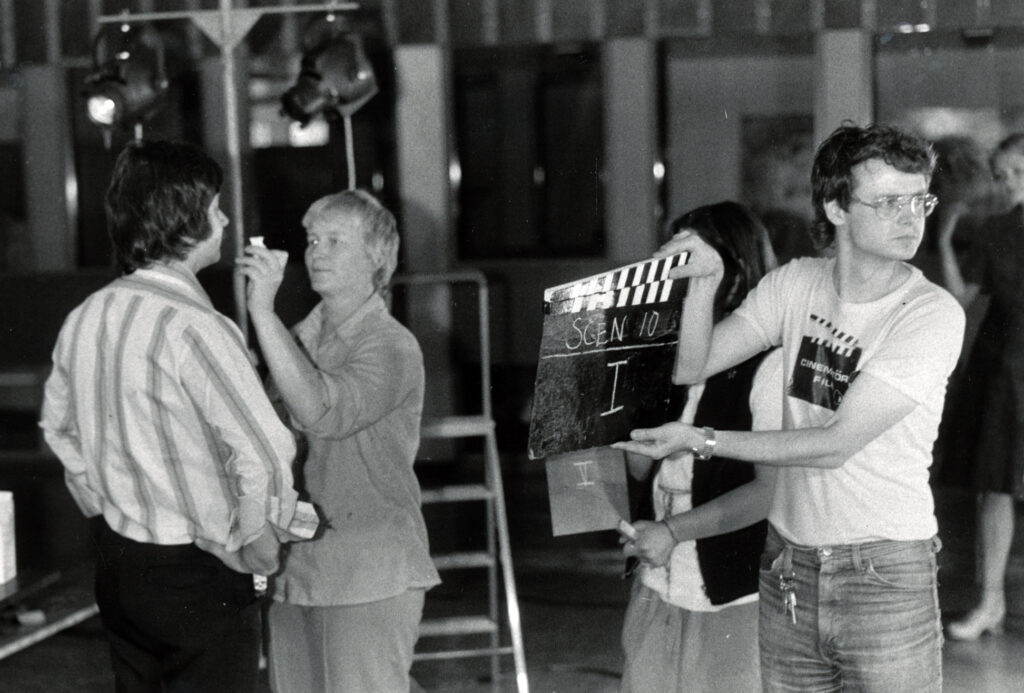

A clapperboard or slate, is an essential tool in filmmaking used to synchronize audio and picture during post-production. The sound of the clapperboard and the picture of it ”closing”.

Editing with scissors and tape.

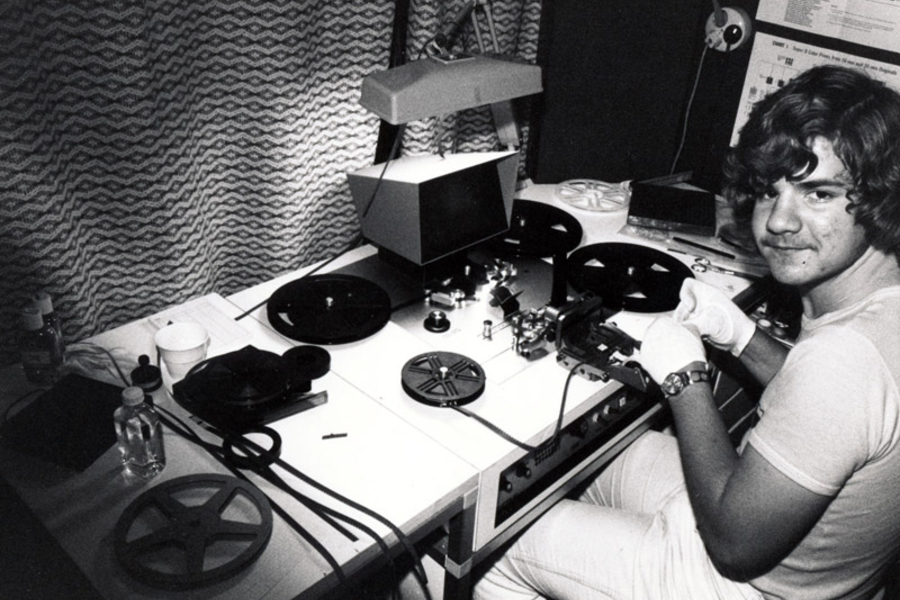

Editing 8mm and 16 mm film in with a professionell technology was a manual and time-intensive process. Editors worked with physical reels of film, cutting and splicing frames together by hand using splicing tape or cement. Moviola or flatbed editing machines, like the Steenbeck, allowed them to view and arrange footage, but precision required patience and skill. Editing sound on perforated magnetic tape (perfotape) was similar to editing film. The perforated tape, synchronized with the film’s frame rate, contained the recorded sound and was manually cut and spliced to match the visual edits. Synchronization was maintained by aligning the tape’s perforations with the film’s frames, allowing sound and picture to stay in sync during playback. This process required patience and meticulous attention to detail, as even small misalignments could lead to noticeable sync issues.

Editing super 8 film with sound on a professionell flatbed editing machine.

In 2015, I had the opportunity to once again use a professional flatbed editing machine for 16mm film while working on a project about filmmaking.

Post-production

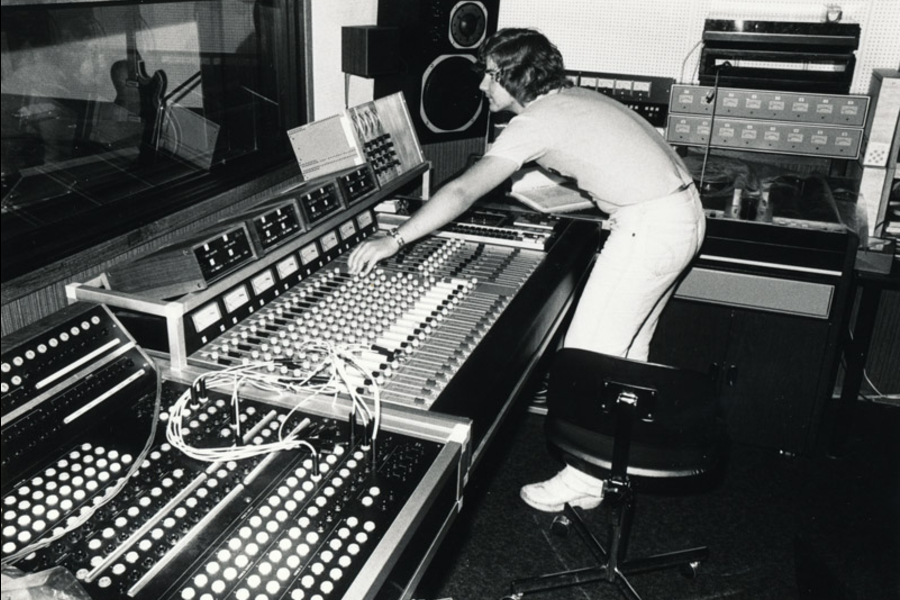

Post-production sound mixing involved a mix of artistry and manual labor. Audio tracks recorded on tape, such as dialogue, music, and sound effects, were mixed in a studio using analog mixing consoles. Mixing involved layering multiple sound elements—cleaning up dialogue, balancing levels, and integrating music and effects into a cohesive whole.

The use of a professional sound studio for film sound mixing was not common for an amateur filmmaker.

Placing Sound on Film

Once the sound mix was complete, the final track needed to be physically attached to the film. A magnetic stripe could be added to the film, allowing sound to be recorded directly onto the strip. Alternatively for 16mm film, an optical soundtrack could be created—a process that converted audio into light waves imprinted alongside the film frames. These methods required expensive equipment and expertise, which were often out of reach for amateur filmmakers.

Building a Low-Budget Movie Set:

Creating a Fake Crematory

Creating a movie set on a low budget is an exercise in pure creativity and resourcefulness. Every element of the set needs to evoke the desired atmosphere while working within the confines of limited funds and materials. When building something as specific and evocative as a fake crematory, the process becomes a perfect blend of art, ingenuity, and problem-solving.

Building the parts to the movie set for a fake crematory on my parents driveway.

Scrap yards, thrift stores, and construction leftovers became treasure troves. Sheets of corrugated metal, pipes mimics the industrial aesthetic of a real crematory. Large wood panels painted with textured finishes worked wonders for creating the illusion of walls.

From the movie ”Utlottad”. (”Out-drawn”)

”Simius”

For the science fiction film ”Simius”, I built a spacecraft set heavily inspired by the iconic Eagle spacecraft from the TV series ”Space 1999”. Using a mix of repurposed materials and detailed miniature work, borrowed electronics from an exhibition at an electronics company and my school’s physics laboratory, I made my spacecraft come to life with blinking lights, buttons, and a sine wave from an oscilloscope.

The movie set is nearly ready for the first take.

Testing lights and back-projections.

Crafting an Outdoor Movie Set:

A Rescue Tent on Another Planet

Creating the illusion of an alien planet on Earth is a thrilling challenge, especially when building a low-budget movie set outdoors. Turning a sandy site into a believable extraterrestrial landscape, complete with a rescue tent, required a mix of resourcefulness, ingenuity, and a keen eye for detail.

The ”rescue tent” is installed on the recording site.

The frame was built from PVC pipes, chosen for their durability and ease to assembly. A reflective, metallic tarp was stretched over the frame, giving it a futuristic and utilitarian look. Details made the set feel alive. Small props around the tent suggested a larger story—scattered ”equipment,” such as survival packs, or tools crafted from repurposed junk and painted to look high-tech.

From the movie ”Simius”.

Standing on that sandy site, seeing an ordinary location transformed into another planet, was immensely satisfying. What started as a patch of Earth became a convincing slice of an alien world through creativity and hard work. The rescue tent stood as a beacon of survival in an inhospitable environment, a tangible reminder of what’s possible when imagination takes the lead.

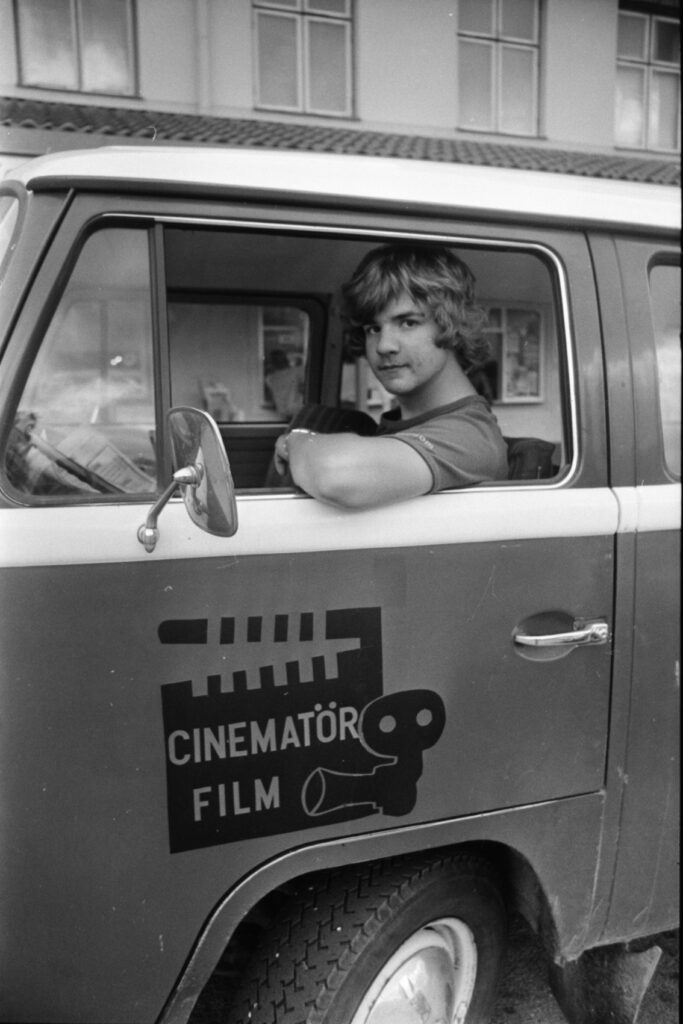

During a film shoot, we were able to borrow a Volkswagen bus to fit all the equipment and the film crew. Our film team’s logo was temporarily placed on the bus door.

The Reward

Despite the struggles, there was magic in the process, and when finally projecting our work onto a screen, it brought an unparalleled sense of accomplishment. The constraints pushed creativity, forcing us to innovate with what we had. Every completed film was a testament to perseverance and passion—a tangible artifact of countless hours of work. Filmmaking in those decades was an art form shaped by its limitations, and for those who braved the challenges.

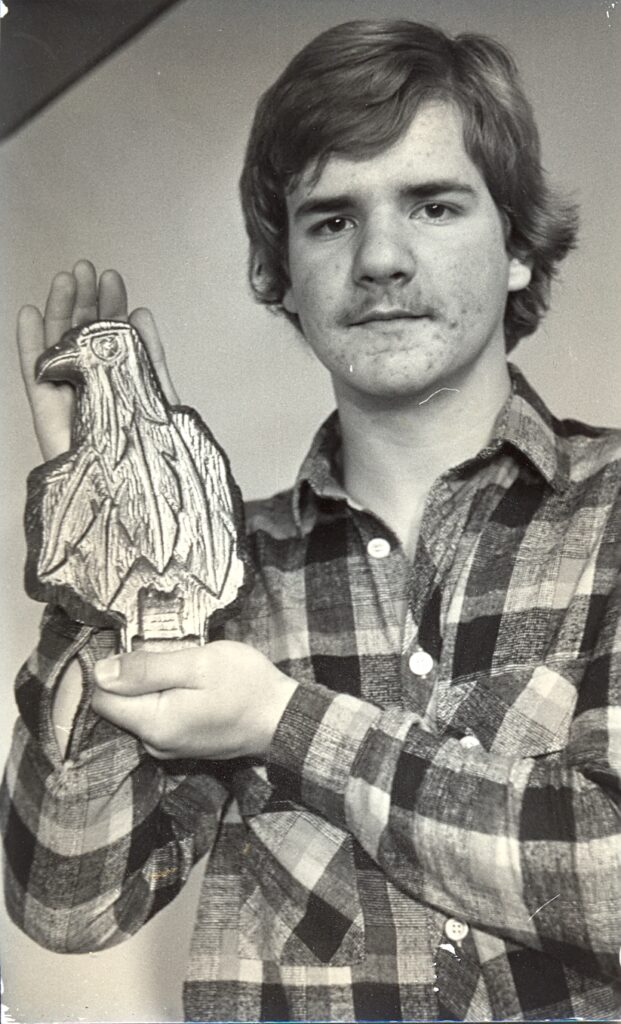

The Film-eagle award for ”Simius”.

I received several awards for my films at festivals organized by Värmlands Filmförbund, which greatly inspired me. The recognition motivated me to continue creating and led to the production of many more movies, fueling my passion for filmmaking.

Screening

Screening Super 8 film for a large audience was a unique experience, but it came with challenges. The poor sound quality and dim lighting often made it hard to fully immerse the audience, and the projector’s rhythmic ”clattering” was a constant distraction in the background. Despite these limitations, sharing my new movie with a large audience back then felt incredibly special. It was a rare opportunity to see people’s reactions in real time, and the excitement of presenting something personal to a crowd was unmatched. In contrast to today, where films can reach millions instantly on platforms like YouTube, back then, a large audience was a much more intimate and impactful experience. The connection with the viewers felt more direct and tangible, making it a memorable moment in the filmmaking journey.

Showing Super 8 film in a cinema was very special, as the projector’s light rarely provided enough brightness to project a clear image on the white screen from the projection room.

Today, the mix of projector noise and the film’s soundtrack creates a nostalgic, raw atmosphere, adding to the charm of the experience for me. But back then, it was just annoying.